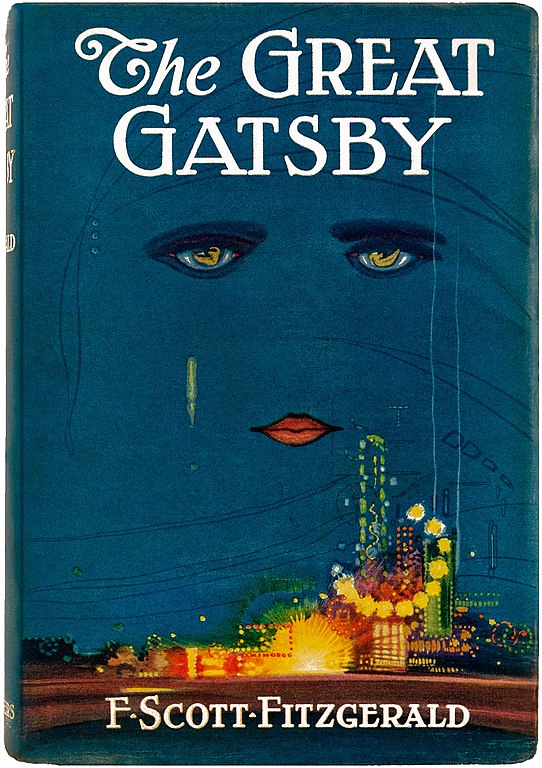

In 1925, upon publication, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s masterpiece novel The Great Gatsby, now considered a classic, caused barely a ripple. It took a while for the literary world to realize its worth.

This artistic embroidery of the tragic love story of Jay Gatsby has often been labelled as the Great American Novel. A few years before the publication of the book, in a letter to Max Perkins (Scribner’s editor), Fitzgerald wrote, “I want to write something new- something extraordinary and beautiful and simple plus intricately patterned.” Just after several years, his wish turned out to be a reality. The ‘Jazz Age,’ as Fitzgerald coined it, in the go-go twenties, with its social upheaval and prodigality, was masterfully portrayed in this novel.

Having returned from the First World War, Nick Carraway, the narrator, moved to West Egg in Long Island, intending to pursue a job as a bond salesman. Within his vicinity lives the mysterious millionaire Jay Gatsby who throws lavish parties for strangers and celebrities from all over the city. Invited to one of those parties, Nick discovers all these were a mere attempt to draw the attention of his cousin Daisy Buchanan. As the readers dive deeper into the story, they find that Gatsby’s life revolves around only one desire: to be united with Daisy, which finally vanishes away with the poignant death of the Protagonist.

At the beginning of the novel, Nick Carraway starts with one of his father’s bits of advice: “Whenever you feel like criticizing anyone… just remember that all the people in this world haven’t had the advantages that you’ve had.” Having taken this advice seriously, he became “inclined to reserve all judgments,” though it made him “the victim of not a few veteran bores.” However, his mention of ‘veteran bores’ only proves that stamping out the impulse or the desire to ‘judge’ is toilsome.

In the first chapter, we see that Tom and Daisy spent a year in France for no definite reason after their marriage and “then drifted here and there unrestfully.” Though Daisy confirmed that moving to the East Egg was permanent, Nick didn’t believe it. He “felt that Tom would drift on forever.” Here we see the Lacanian notion of desire: “Desire, a function central to all human experience, is the desire for nothing nameable. And at the same time, this desire lies at the origin of every variety of animation. If being were only what it is, there wouldn’t even be room to talk about it. Being comes into existence as an exact function of this lack.” ( Lacan, 1991)

The same scenario can be seen in the case of Gatsby. Though he had already achieved wealth, money, and power, he still had the desire to get Daisy back. And that was not all of it. Gatsby wanted Daisy to proclaim that she never loved Tom and divorce him. According to Zizek: “..the realization of desire does not consist in its being “fulfilled,” “fully satisfied,” it coincides rather with the reproduction of desire as such, with its circular movement.” (Zizek, 1991)

Additionally, Lacan says, “The object of man’s desire is essentially an object desired by someone else.” In this novel, we stumble upon many situations that support this theory. While reminiscing about their first meetings, Gatsby told Nick that his desire for Daisy was instigated by the fact that she was desired by many. “He found her excitingly desirable� It excited him, too, that many men had already loved Daisy-it increased her value in his eyes.” (The Great Gatsby, p.149). Even later in the novel, as soon as Tom discovers Daisy’s love for Gatsby, he becomes ardent about winning her back.

According to Jaques Lacan, human reality is a combination of three inseparable levels- Symbolic, Imaginary, and Real. This symbolic level acts as the locus for language and law.

But whose language? For example, I am saying that Bengali is my language. However, my consent was not taken while fixing the rules and structure of this language. This means I literally ‘fell’ into a language structure that had already been created. And this language has been gyrating over our heads from the background through various attachments of customs, restrictions, and culture right from the word go. Lacan named this level ‘the big Other’ due to its ability to hold sway over the subject without being a part of it from behind under the masquerade of the symbolic order.

“..This symbolic space acts like a yardstick against which I can measure myself. This is why the big Other can be personified or reified in a single agent: ‘God’ who watches over me from behind, and overall real individuals, or the Cause that involves me ( Freedom, Communism, Nation) and for which I am ready to give my life.” (Zizek, 2007 )

According to Jaques Lacan, human reality is a combination of three inseparable levels- Symbolic, Imaginary, and Real.

In this novel, the eyes of the oculist Doctor T. J. Eckleburg on the signboard are a symbolic representation of that sub rosa big Other, which remains vigilant throughout the story, controlling, from behind, human desires and all activities regarded to it. In the case of the narrator Nick Carraway, who had been raised in a middle-class family, we see that even he was not exempt from the pursuit of the American dream (the belief that anyone, regardless of race, class, gender, or nationality, can be successful in America). Though he didn’t appreciate prodigality, he couldn’t ignore the pleasure he obtained from garish parties in New York. So, he was “within and without, simultaneously enchanted and repelled.”

Lacan’s Symbolic level is all about desire. As soon as we enter the realm of language, our desire inextricably gets linked to the play of language. Desire is the block that staves off our contact with the real. And thus, its purpose is not to obtain the object of desire but to reproduce itself. In this story of Fitzgerald, Protagonist Jay Gatsby was unaware of the fact that desire is not something to be fulfilled. But Gatsby was so hopeful, and “his dream must have seemed so close that he could hardly fail to grasp it.” And finally, Gatsby’s tragic death reminds us of Lacan’s notion about death: Each drive is a death drive. But that’s no matter; our desires live on. Fitzgerald’s artistic expression: “to-morrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther. So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”

For all latest articles, follow on Google News

For all latest articles, follow on Google News