Would you like to see the tolerance of ambiguity as part of your repertoire of civic skills? Whether we like it or not, the attribute seems to be demanded by authorities, although not overtly, in many parts of the world.

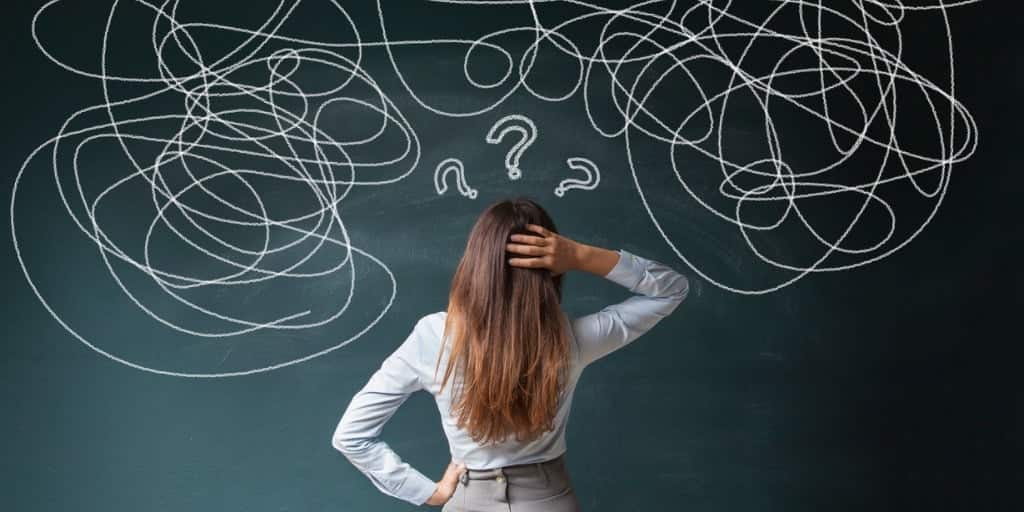

What is tolerance of ambiguity? Ambiguity is a psychological construct that has been widely used in various fields of interest. As a personality trait, it refers to the ability to tolerate uncertainty, inconsistency or lack of clarity in information, input or stimuli. Apparently, ambiguity in instructions may frustrate us if we have to act on such input. It may give a sense of insecurity to those who like to see the world in clear black-and-white terms. However, a lot of research has presented ambiguity tolerance as a desirable quality, which can be linked to creative decision-making and problem-solving in workplaces or organisations.

How ambiguity works is relatively simple to explain. When there is ambiguity, or open-endedness, or a range of options in stimuli, employees feel invited to utilise their lateral thinking and creative potential, which may lead to innovative and efficient decisions. The higher level of cognitive demand in such situations recognises the expertise and agency of people at various levels of the official hierarchy.

I was introduced to tolerance of ambiguity while pursuing my academic work in the field of language teaching. Like many other fields, second language teaching has promoted ambiguity tolerance as a desirable learner’s attribute, which can be correlated with efficient learning and positive learning outcomes. In learning a second/foreign language, our goal is to master a new language system together with the many conventions of the use of various linguistic features and resources for different communication purposes in different situations. Although languages are generally rule-governed, there are many exceptions to rules. The novelty or strangeness of rules, their exceptions and inconsistences, and the peculiarities of their real-life application may frustrate you, instigating you to give up the linguistic endeavour altogether. What is needed is tolerance of inconsistency in the target-language input. The ultimate reward of this ‘good language learner’ trait is your likely discovery of how things work in the end, and your development of the ability to use the language for whatever purposes you may have set for yourself.

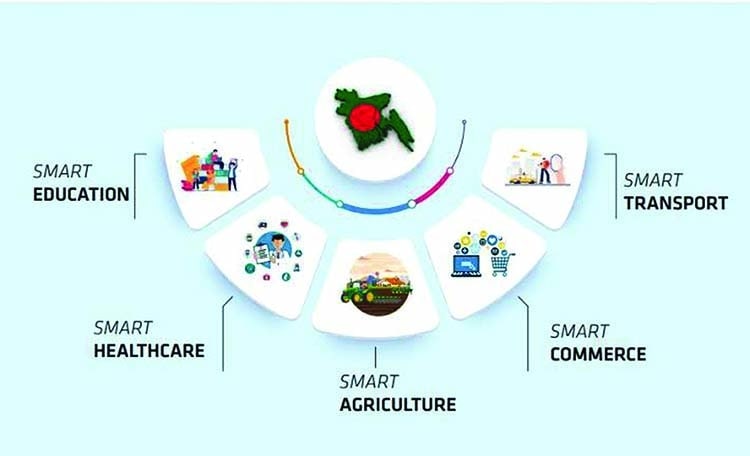

If ambiguity tolerance is associated with desirable outcomes in language learning, workplaces and other areas of life, should it not be desired in civic life as well? The answer may depend on the kind and degree of ambiguity and the intention behind it. Ambiguity generally refers to a lack of clear directions in propositions leading to their multiple interpretations and enactments. However, a higher degree of ambiguity in propositions or actions may entail remarkable inconsistencies, contradictions, irregularities and exceptions to rules that may remind us of ‘double-standards’. More crucially, it will depend on the motive behind the ambiguity, which may range from the benign or innocuous to the deliberate and unashamed pursuit of individual or collective self-interest. We also need to appreciate the scope of civic life, which is much wider than any professional domain. Finally, the kinds of issues that are relevant to the public sphere and the consequences of a high-degree of ambiguity in these issues may not be ignored.

What are some of the kinds of ambiguities that we are invited to tolerate as global and local citizens? We may be able to consider only a few.

For example, you may have noted the desperate attempts by global powers in the past years to stop one particular country from attaining nuclear capability, while such capability attained by another nation is rarely tabled for discussion. You may appreciate one country’s condemnation of human rights violations in one place but you may have to do so by tolerating their silence — or even material or ideological support of such violations — in another place. And then, there is the near-classic case of the same crime being given different labels depending who the perpetrators are and where they come from.

Locally, there are many ambiguities or inconsistencies, which we may be invited to tolerate. As a nation having received material and moral support from another nation during our war of independence, we may take this helping nation as our role-model and draw the logical conclusion that helping other nations seeking freedom is a moral obligation. Your logic may also tell you that a nation that likes to help others will help all others. However, that may be a faulty logic reflective of an intolerant attitude. In other words, you need to understand the relationship of help and support case by case, without referring to general principles or drawing general conclusions. This may be the demand for ambiguity tolerance.

Ambiguity tolerance may also mean attesting to the peaceful co-existence of extremes. You can testify how secularism and state-religion become bedfellows, and how the same person can be most secular and most pious at the same time, only if you are tolerant. Ambiguity tolerance may mean not asking why the same dice produces different shapes of bread; or why the same action produces different rewards for different people. It refers to your ability to ignore such silly questions as why the language that you use has the potential to harm others but my use of the same language may not cause any such harm; or why the fire that you kindle burns but my fire brings coolness on a summer day.

It should be acknowledged that tolerance of ambiguity also depends on who we are and where we belong in the world. There are those who may not read ambiguity in ambiguities, while others may be more perceptive. Tolerance of ambiguity applies only to those in the latter category. But you don’t have to tolerate ambiguity, if you can afford to tolerate a small price.

For all latest articles, follow on Google News

For all latest articles, follow on Google News